The Enduring Legacy of Mughal Architecture in India

The history of South Asia is marked by overlapping dynasties, artistic traditions, and cultural syntheses. Among these, the Mughal dynasty (16th–18th centuries) occupies a distinctive position, particularly for its architectural achievements. Mughal rulers not only consolidated political authority across a vast territory but also articulated imperial vision through monumental architecture. These works were never mere edifices; they embodied layered meanings of sovereignty, cosmology, and cultural identity. As Catherine Asher observes, Mughal architecture became “a language of power” that simultaneously communicated beauty and legitimacy (Asher 1992).

A Cosmopolitan Aesthetic

Mughal architecture is notable for its synthesis of Persian, Islamic, Central Asian, and indigenous Indian traditions. This was not accidental but rather a deliberate imperial strategy to present the empire as a cosmopolitan entity. Domes and minarets symbolized sovereignty, pietra dura inlays suggested refinement and wealth, and geometric precision reflected both mathematical sophistication and metaphysical notions of divine order. The charbagh garden design, inspired by Persian cosmology, was especially significant: it translated theological ideas of paradise into material form (Asher 2006). In this way, the Mughal aesthetic not only harmonized diverse traditions but also elevated architecture into a statement of universal rule.

Architecture as Power and Ideology

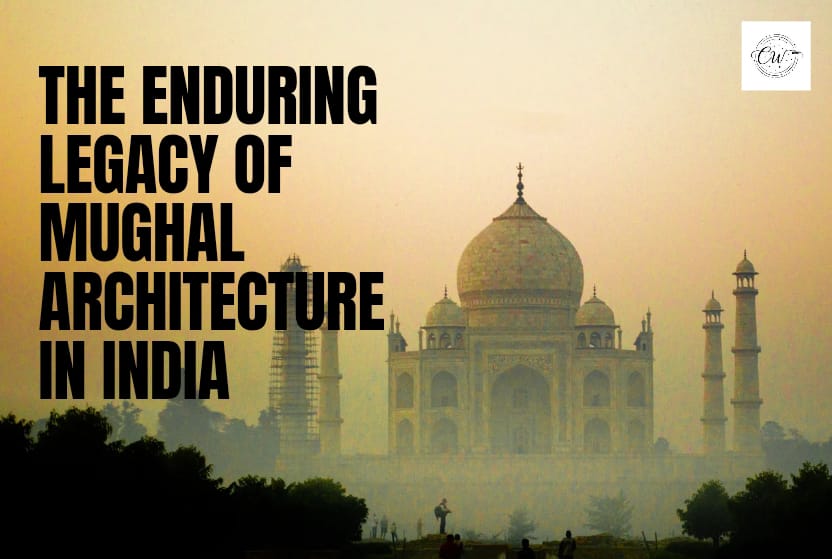

The monuments produced under Mughal patronage demonstrate the interplay of art and politics. The Taj Mahal, often celebrated as a monument to love, has been reinterpreted by Ebba Koch as a political statement that fused personal commemoration with dynastic grandeur (Koch 2006). The Red Fort in Delhi, with its fortified walls and ceremonial halls, projected Shah Jahan’s centralized authority and cultivated an image of permanence. Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar’s visionary but short-lived capital, integrated Hindu and Islamic motifs in ways that scholars interpret as reflective of his inclusive political strategies (Nath 1985). Similarly, Humayun’s Tomb established a new template for imperial mausoleums, blending Persian influences with Indian craftsmanship and laying the groundwork for later masterpieces (Asher 1992).

Debates on Meaning and Function

Interpretations of Mughal architecture remain contested. Some scholars emphasize the spiritual dimension, reading symmetry, gardens, and cosmological motifs as reflections of divine order (Asher 2006). Others highlight the political dimension, framing these monuments as instruments of imperial propaganda (Koch 2006). Finbarr Flood suggests a more fluid approach, arguing that Mughal monuments acquired shifting meanings over time, functioning differently across audiences and historical contexts (Flood 2009). This scholarly debate underscores the dual nature of Mughal architecture: at once transcendent and pragmatic, devotional and political.

Influence Beyond the Mughal Period

The Mughal architectural vocabulary continued to shape South Asian aesthetics well beyond the dynasty’s decline. During the colonial period, Indo-Saracenic architecture adapted Mughal motifs—domes, arches, and decorative façades—to project cultural continuity while reinforcing British authority (Metcalf 1989). In contemporary India, Mughal-inspired motifs remain central to the design of public institutions and heritage hotels, where they serve as markers of prestige and cultural authenticity. Tourism, particularly around the Taj Mahal, ensures that Mughal architecture retains global relevance, embedding itself in circuits of cultural memory and economic value.

Conclusion

The architectural legacy of the Mughals exemplifies the intersection of aesthetics, politics, and spirituality in premodern South Asia. These monuments were not static symbols of beauty but dynamic instruments of ideology, projecting imperial authority while articulating deeper cosmological and cultural visions. Scholarly debates—oscillating between interpretations of paradise, propaganda, and pluralism—highlight the richness of their meanings. The endurance of this architectural tradition, through colonial adaptation and contemporary appropriation, testifies to the capacity of Mughal monuments to transcend historical context. Ultimately, they endure not merely as relics of a dynasty but as lasting symbols of cultural synthesis and human creativity.